©

Margaret Schuler

Adopted and Maintained by PARTNERS FOR LAW IN DEVELOPMENT (PLD INDIA) as part of the digital Feminist Law Archives.

Adopted and Maintained by PARTNERS FOR LAW IN DEVELOPMENT (PLD INDIA) as part of the digital Feminist Law Archives.

Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law & Development

Planning

In early 1986 OEF International received a grant from the Ford Foundation for the purpose of organizing a preparatory process leading up to and including a WLD conference in the Asia Pacific region. The grant covered travel and conference costs, materials preparation and organizing costs.

As a starting point, I assembled an interim regional planning committee, composed of those who had participated in the Nairobi Forum the previous year. The interim committee included:

- Radhika Coomaraswamy (Sri Lanka),

- Savitri Goonesekere (Sri Lanka),

- Farida Ariffin (Malaysia),

- Virada Somswasdi (Thailand),

- Irene Santiago (Philippines),

- Mere Pulea (Fiji),

- Ranjana Kumari, (India)

- Rani Jethmalani, (India) and

- Lotika Sarkar (India), and

- Margaret Schuler of OEF/WLD.

Reiterating the recommendations from the Nairobi WLD Forum, the committee spelled out the need for a “WLD Forum” for the Asia/Pacific region. They analyzed the most critical issues facing women and the responses by government and non-governmental organizations to those needs. Guided by this analysis, the interim committee recommended that the functions of the future Asia Pacific Forum on WWLD would be to:

- share information about substantive issues and strategies through newsletters and occasional papers;

- organize seminars at regional and sub-regional levels on topics of common interest;

- develop broader understanding of issues, improve skills, and strengthen network linkages in the form of internships and study tours for project organizers and grassroots workers;

- develop and exchange materials, methods and techniques;

- mobilize member organizations in response to both emergency situations and critical issues constituting an imminent threat to women's rights;

- monitor regional and local developments;

- develop model legislation.

- the effects of law, religion, and custom on women;

- the role of law in promoting or combatting violence toward and exploitation of women, and;

- women's economic rights.

Prior to the conference we sent some 60 invitees the proposal for establishing the new regional organization and a survey of their activities and opinions regarding priorities for action and the potential role of APWLD. In preparation, these activists and academics held country level meetings where feasible to discuss the potential for the new organizaton and the issues they felt needed to be addressed. In this way, they arrived at the conference ready to fully engage.

The Conference

In December 1986, fifty-two women from a dozen Asian

and Pacific countries—lawyers, activists and academicians—gathered

together to discuss substantive and programmatic issues related to women and the

law and to devise or identify effective strategies for improving women's rights

in the region. The participants met first in Manila and then went by bus to a

conference center in Tagaytay, a town south of Manila on the Philippine island

Luzon. In this beautiful setting, on a ridge above Taal Volcano, an active

volcano surrounded by Taal Lake, participants also embarked on the serious

venture of establishing the Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law and

Development.

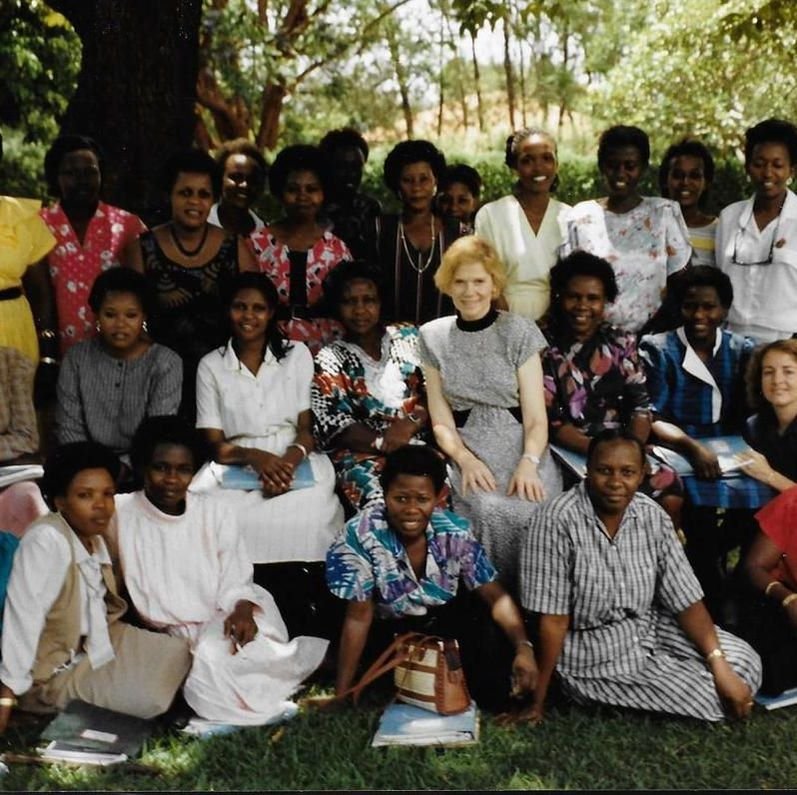

Photos from the APWLD

Conference

( For a more complete discussion of the issues and strategies relating to the Asia region at the conference, see: APWLD Issues and Strategies 1986)

Substantive Discussion

For the first three days, conferees attended plenary sessions and one or more of the twelve designated workshops. They presented papers and participated in in-depth discussions about the substantive themes of 1) women’s rights and religion, 2) violence and exploitation of women and 3) economic and labor rights. Under the topic of law, religion and women’s rights, the workshops covered the following issues.

- religious influence on the law,

- the effect of religious fundamentalism on personal law,

- the dichotomy between customary and state law and

- strategies to confront regressive influences on legal systems in the region.

- domestic violence and its causes,

- rape and sexual harassment,

- prostitution,

- reproduction as violence and

- strategies to confront each of these issues.

Inheritance and matrimonial rights

- land rights,

- free trade zones

- the informal sector

- migrant workers and

- strategies to confront problems in each of these areas.

Establishment of APWLD

On the final day of the conference, participants proceeded with the creation of the Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law, and Development. They agreed that APWLD would primarily facilitate processes and activities designed to raise the legal status of women, especially those in disadvantaged circumstances. They drew up a set of organizing principles stating that the APWLD would be an independent and autonomous, non-governmental, non-profit organization and that membership would be open to Asian and Pacific women's NGOs committed to its objectives.

The Goal of APWLD

Empowering women in the Asia Pacific region to

use the law as an instrument of social change for equality and

development.

The assembly framed the primary goal of APWLD as empowering women in the Asia Pacific region in the use of law as an instrument of social change for equality and development, enabling women to use law and legal institutions in furtherance of the Forum's objectives, and promoting the basic concept of human rights in the region as enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

To fulfill this goal, the assembly also formulated several specific objectives:

- To work towards the development of a model code of values which reflects women's quest for equality and justice;

- To urge national governments to ratify and effectively implement the U.N. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (1981);

- To work towards the realization of the full potential of women and their position of equality within the family structure and society;

- To promote women's economic rights to ensure that they have equal access to all productive resources;

- To enhance women's participation and capacity to shape macroeconomic development strategies in their own country and in the region;

- To promote processes which will ensure women's equality in political participation;

- To facilitate and strengthen interaction among individuals, groups, and countries committed to the overall objectives;

- To share information, expertise, experiences, and resources to develop and strengthen individual and collective action;

- To express solidarity and to mobilize members of the Forum and public opinion in cases of exploitation of women and violations of their rights.

The Steering Committee was given responsibility for guiding the development and implementation of the program and to be accountable to the membership for the faithful implementation of the functions of the Asia Pacific Forum as outlined. The committee members elected in 1986 were: Mere Pulea (Fiji), Rani Jethmalani (India), Farida Ariffin (Malaysia), Emelina Quintilian (Philippines), Asma Jahangir (Pakistan), Radhika Coomaraswamy (Sri Lanka), and Virada Somswasdi (Thailand).

At the first meeting held immediately after the conference, the APWLD steering committee discussed the tasks that needed to be done to bring the organization to frution. They asked me if I would continue to assist them in the development of the APWLD program, most immediately with proposal development, funding contacts and program planning. I agreed.

Participants

BANGLADESH

Roushan Jahan Women for Women

Salma Sobhan Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC)

INDIA

Rani Adwani Self-Employed Women's Association (SEWA)

Nandini Azad New Delhi, India

Jyotsna Chatteiji Joint Women's Programme

Ranjana Kumari Center for Social Research

Manjula Rathore Benares Hindu University

Josna Roy Center for Social Recearch

Nalini Singh Journalist

INDONESIA

Luisa Gandi Fakultas Hukum, Universitas Indonesia

Saparinah Sadli LliuWK (Women's Legal Services Project)

Amartiwi Saleh Legal Aid Lawyer

Nani Yamin LKBuWK (Women's Legal Services Project)

JAPAN

Miyoko Shiozawa Center for Asian Women Workers

MALAYSIA

Noor Farida Ariffin Association of Women Lawyers

Lim Kah Cheng Association of Women Lawyers

Irene Fernandez Women's Development Collective

NEPAL

Silu Singh Women's Legal Services Project, Nepal Women's Organization

Shanta Thapalia Faculty of Law, Trihbuvan University

PACIFIC

Shamima Ali Women's Crisis Center Suva, Fiji

Mere Pulea Mere Pulea and Associates Republic of Nauru

PAKISTAN

Asma Jahangir AGHS Law Associates

Hina jilani AGHS Law Associates

Rashida Patel Pakistan Women Lawyers Association

PHILIPPINES

Alice Canonoy-Morada Dentral Visayas Regional Projects

Marilyn Cepe BATAS (Center for People's Law)

Mariflor Parpan MATAGU

Soledad Perpinan Third World Movement Against the Exploitation of Women

Jing Porte Women's Center Quezon City

Emelina Quintillan PILIPINA Legal Resources Center Davao

SRI LANKA

Radhika Coomaraswamy International Centre for Ethnic Studies

Nimalka Fernando National Christian Council

Savitri Goonesekere Faculty of Law, Open University

Manouri Muttetuwegama Attorney

THAILAND

Chantawipa Apisuk EMPOWER Bangkok

Malee Pruekpongsawalee Faculty of Law, Thammaset University.

Virada Somswasdi ChiangMai University, Faculty of Social Sciences

OEF/WLD

Margaret Schuler, WLD Program Director

Robin Forrest, WLD Program Associate

Nancy Rubin, OEF Board Member

* In addition there were observers representing the Ford Foundation and the Latin America and Africa WLD networks.

Roushan Jahan Women for Women

Salma Sobhan Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC)

INDIA

Rani Adwani Self-Employed Women's Association (SEWA)

Nandini Azad New Delhi, India

Jyotsna Chatteiji Joint Women's Programme

Ranjana Kumari Center for Social Research

Manjula Rathore Benares Hindu University

Josna Roy Center for Social Recearch

Nalini Singh Journalist

INDONESIA

Luisa Gandi Fakultas Hukum, Universitas Indonesia

Saparinah Sadli LliuWK (Women's Legal Services Project)

Amartiwi Saleh Legal Aid Lawyer

Nani Yamin LKBuWK (Women's Legal Services Project)

JAPAN

Miyoko Shiozawa Center for Asian Women Workers

MALAYSIA

Noor Farida Ariffin Association of Women Lawyers

Lim Kah Cheng Association of Women Lawyers

Irene Fernandez Women's Development Collective

NEPAL

Silu Singh Women's Legal Services Project, Nepal Women's Organization

Shanta Thapalia Faculty of Law, Trihbuvan University

PACIFIC

Shamima Ali Women's Crisis Center Suva, Fiji

Mere Pulea Mere Pulea and Associates Republic of Nauru

PAKISTAN

Asma Jahangir AGHS Law Associates

Hina jilani AGHS Law Associates

Rashida Patel Pakistan Women Lawyers Association

PHILIPPINES

Alice Canonoy-Morada Dentral Visayas Regional Projects

Marilyn Cepe BATAS (Center for People's Law)

Mariflor Parpan MATAGU

Soledad Perpinan Third World Movement Against the Exploitation of Women

Jing Porte Women's Center Quezon City

Emelina Quintillan PILIPINA Legal Resources Center Davao

SRI LANKA

Radhika Coomaraswamy International Centre for Ethnic Studies

Nimalka Fernando National Christian Council

Savitri Goonesekere Faculty of Law, Open University

Manouri Muttetuwegama Attorney

THAILAND

Chantawipa Apisuk EMPOWER Bangkok

Malee Pruekpongsawalee Faculty of Law, Thammaset University.

Virada Somswasdi ChiangMai University, Faculty of Social Sciences

OEF/WLD

Margaret Schuler, WLD Program Director

Robin Forrest, WLD Program Associate

Nancy Rubin, OEF Board Member

* In addition there were observers representing the Ford Foundation and the Latin America and Africa WLD networks.

Program Development

Once again, like in Nairobi, with the

conclusion of the process and the elaboration of a clear vision for the future,

the founding members were faced with a challenge. They had laid out objectives,

but there was no funding yet for the program, no office and no personnel to

organize it within the region. Proposals needed to be prepared, funding secured,

legal incorporation of the organization effected, staff hired, etc. A major

challenge was the fact of geographical distances separating the steering

committee members. They needed speedy and reliable communication among them if

they were to accomplish the additional program elaboration that was required.

Doing so in the era before internet when even fax wasn't yet common was

challenging, indeed, and timing was a delicate matter at that point. If

action was not taken quickly, enthusiasm could wane. Donors needed confidence

that the commitment to move forward was sufficiently strong to warrant their

backing.

Our WLD program at OEF, of course, committed to do whatever was possible to see this through. I approached several European donors that had funded various aspects of the development process. They said they were interested but were awaiting a proposal from APWLD. I also approached the Ford Foundation again, the major donor of the preparatory phase and the conference. To my surprise I was told, "APWLD doesn't yet have a track record. What is needed is evidence that the leadership of the organization is coalescing." Having committed a good amount of energy and time to the effort myself, I wanted to see APWLD move forward effectively. I realized that although I would play a supportive role, the steering committee of APWLD had to be fully engaged. At that moment the program proposal needed further input from the steering committee, which was difficult to achieve. The members were living in seven different countries and had full time jobs themselves. I felt it was important to bring the group together again primarily to refine the program proposal they would advance to donors for funding. Once the proposal was in place, I was confident that donor agencies would be ready to step up. But there were no resources at that point to gather the group together again. My challenge was to find a way.

The opportunity came in April 1987 when I was invited to travel to Philadelphia and participate in a planning group convened by the mayor’s office. They wanted to organize a series of events to commemorate the bicentennial of the US Constitution later that year, including an international conference. That sounded like an interesting prospect and I determined to get WLD-related participants invited as speakers and have their travel paid for by the city of Philadelphia. They could subsequently have their own meeting, piggy-backing on the Philadelphia conference.

And indeed, it did work out that on my recommendation several members of the APWLD steering committee were invited by the city of Philadelphia to speak at the conference, with a commitment to cover their travel expenses. OEF covered the slack for the others and in the end most made it to Philadelphia. The two-day Philadelphia conference itself was not very well organized and a little confusing. Some of the APWLD participants were disappointed with their panels and the quality of the discussion. Worse even, was the arrangement for accommodations. The invitees were put up in university student housing and given very little per diem. No doubt, the Philadelphia conference commemorating the US Constitution was less than spectacular, but that was beside the point. Despite the difficulties, the people relevant to the task of building APWLD were together and able to move the organization forward during the following week.

The Bryn Mawr Meeting

Following the conference, APWLD was the recipient of a generous gift, this one from Bryn Mawr College, a prestigious women's college located outside Philadelphia. Fortunately, it was summer and students were not in residence, so at WLD/OEF's request Bryn Mawr graciously offered the college as a venue for the APWLD meeting including lodging for all participants. So, once again, the APWLD Steering Committee was able to efficiently work together to advance its goals--even though the meeting took place half way around the world from Asia.

At that meeting, the constitution of APWLD was set, its program more clearly laid out and plans for serious fund raising developed. The program they outlined had five major components. communication, education, research, mobilization and monitoring.

Information and Communications. This component of the program would aim at sharing information about substantive issues and strategies. The principle means to share information would be a regional newsletter containing information on the extent and scope of work relating to women's rights by women NGOs in the region and major socio-legal issues relating to women in member countries. In addition, occasional papers, products of APWLD educational work and research, conference presentations, would be published and a comprehensive bibliography of publications (books, articles, studies, training materials, etc.) relating to the field of women, law, and development compiled.

Education and Training of WLD Activists. The educational component of the program, designated as a priority area, proposed to develop broader understanding of the issues and strategies among its members to improve their skills, and to strengthen network linkages. This was viewed as consistent with the objectives of deepening the link between theory and practice and increasing the mobilizing capacity of the network. Educational experiences aimed to take several forms.

Monitoring. Another important component proposed was monitoring of national WLD strategies in the region, including documenting the reasons for their successes and failures. This component also included monitoring the implementation of the U.N. Convention for the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women

With the proposal in good shape at this point and a program clarified, the organization was in a position to the move forward with the implementation of its vision.

Our WLD program at OEF, of course, committed to do whatever was possible to see this through. I approached several European donors that had funded various aspects of the development process. They said they were interested but were awaiting a proposal from APWLD. I also approached the Ford Foundation again, the major donor of the preparatory phase and the conference. To my surprise I was told, "APWLD doesn't yet have a track record. What is needed is evidence that the leadership of the organization is coalescing." Having committed a good amount of energy and time to the effort myself, I wanted to see APWLD move forward effectively. I realized that although I would play a supportive role, the steering committee of APWLD had to be fully engaged. At that moment the program proposal needed further input from the steering committee, which was difficult to achieve. The members were living in seven different countries and had full time jobs themselves. I felt it was important to bring the group together again primarily to refine the program proposal they would advance to donors for funding. Once the proposal was in place, I was confident that donor agencies would be ready to step up. But there were no resources at that point to gather the group together again. My challenge was to find a way.

The opportunity came in April 1987 when I was invited to travel to Philadelphia and participate in a planning group convened by the mayor’s office. They wanted to organize a series of events to commemorate the bicentennial of the US Constitution later that year, including an international conference. That sounded like an interesting prospect and I determined to get WLD-related participants invited as speakers and have their travel paid for by the city of Philadelphia. They could subsequently have their own meeting, piggy-backing on the Philadelphia conference.

And indeed, it did work out that on my recommendation several members of the APWLD steering committee were invited by the city of Philadelphia to speak at the conference, with a commitment to cover their travel expenses. OEF covered the slack for the others and in the end most made it to Philadelphia. The two-day Philadelphia conference itself was not very well organized and a little confusing. Some of the APWLD participants were disappointed with their panels and the quality of the discussion. Worse even, was the arrangement for accommodations. The invitees were put up in university student housing and given very little per diem. No doubt, the Philadelphia conference commemorating the US Constitution was less than spectacular, but that was beside the point. Despite the difficulties, the people relevant to the task of building APWLD were together and able to move the organization forward during the following week.

The Bryn Mawr Meeting

Following the conference, APWLD was the recipient of a generous gift, this one from Bryn Mawr College, a prestigious women's college located outside Philadelphia. Fortunately, it was summer and students were not in residence, so at WLD/OEF's request Bryn Mawr graciously offered the college as a venue for the APWLD meeting including lodging for all participants. So, once again, the APWLD Steering Committee was able to efficiently work together to advance its goals--even though the meeting took place half way around the world from Asia.

At that meeting, the constitution of APWLD was set, its program more clearly laid out and plans for serious fund raising developed. The program they outlined had five major components. communication, education, research, mobilization and monitoring.

Information and Communications. This component of the program would aim at sharing information about substantive issues and strategies. The principle means to share information would be a regional newsletter containing information on the extent and scope of work relating to women's rights by women NGOs in the region and major socio-legal issues relating to women in member countries. In addition, occasional papers, products of APWLD educational work and research, conference presentations, would be published and a comprehensive bibliography of publications (books, articles, studies, training materials, etc.) relating to the field of women, law, and development compiled.

Education and Training of WLD Activists. The educational component of the program, designated as a priority area, proposed to develop broader understanding of the issues and strategies among its members to improve their skills, and to strengthen network linkages. This was viewed as consistent with the objectives of deepening the link between theory and practice and increasing the mobilizing capacity of the network. Educational experiences aimed to take several forms.

- Seminars and workshops - These would be organized or convened around topics of common interest. Among the priority topics identified were analysis of the legal systems in the Asia Pacific region and their gender implications, evaluations of legal programs and how they affect women, social development planning, policy-making, lawmaking, and developing forward-looking strategies.

- Inter-organizational exchanges - Another approach to learning is the use of inter-organizational exchanges, either as study tours or internships. This was aimed primarily at the grassroots worker and project organizer.

- Exchange of materials, methods, and techniques.

- Community legal literacy - APWLD proposed to assist women throughout the region to learn more about effective approaches to legal literacy. Through workshops and training sessions APWLD participants would acquire skills in fostering grassroots rights awareness and action.

- judicial decisions with gender implications;

- analysis and examination of gender and developmental implications of legal education and law curricula;

- socio-cultural factors affecting legal activists (why they are legal activists and the hazards/risks they take); and

- model WLD legislation in the AP region.

Monitoring. Another important component proposed was monitoring of national WLD strategies in the region, including documenting the reasons for their successes and failures. This component also included monitoring the implementation of the U.N. Convention for the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women

With the proposal in good shape at this point and a program clarified, the organization was in a position to the move forward with the implementation of its vision.

Organization Development

The Steering Committee chose Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia as the

venue for the regional office. The committee agreed that because of its central

regional location and its cultural and religious diversity, Malaysia would be an

appropriate setting from which to coordinate the programs of the Asia Pacific

Forum. Also, rather than build the infrastructure for the APWLD from scratch, it

was decided to link with a supportive, existing institution. Since the Women's

Programme of the Asia Pacific Development Centre in Kuala Lumpur was compatible

in terms of vision and approach to APWLD, it was anticipated that a substantive

link between the two organizations would be feasible and advantageous. Noeleen

Heyzer, Director of APDC Women's Programme, agreed to support APWLD in its

development, providing not only access to ready-made infrastructure, but

guidance in its development as well.

The steering committee offered the position of regional coordinator to one of its own members, Emelina Quintillan from the Philippines. She accepted the position and relocated to Kuala Lumpur at the end of the year, 1987, one year after the founding conference in Tagaytay. The APWLD office, which they called the secretariat, opened in January, 1988 in the Asia Pacific Development Center building, two stories up from Noeleen Heyzer's office and the APDC Women's Programme. Shanthi Dairium, an activist with Women's Aid in Kuala Lumpur joined Emelina on staff as program associate. In my consultative role, I spent several weeks during 1988 in Kuala Lumpur assisting the fledging staff in their task of organization and program development.

During its first year the APWLD staff divided its work between institution-building activities and program implementation. Its list of priorities for 1988 included developing effective communication between staff and steering committee and fund-raising for the administrative expenses needed for its operation. Initially, the tasks of the secretariat centered on:

In addition to gathering information and data about country situations, pertinent to threats against women's rights, the APWLD collaborated with 25 other women's organizations filing a suit with the Supreme Court of India against 'Sati'. In another gesture of solidarity, APWLD supported its Pakistani Steering Committee member, Asma Jahangir, who provided legal services in seeking the release of women, men, and children who were bonded brick kiln workers in Lahore, Pakistan. With a view to awareness raising and mobilization during its first year, APWLD drafted and disseminated a resolution calling on all women to be vigilant against retrogressive policies and enjoining parliamentarians to assume their duty of safeguarding the rights won by and for women. The resolution was disseminated widely and published in newspapers and newsletters across the region. Staff and steering committee members also provided technical assistance to local organizations in developing tools for policy analysis, setting up legal literacy programs, providing advice and referrals on matters related to women and development, law and development, and women and law, and facilitating the exchange of materials and inter-organizational meetings among the members.

One of the objectives agreed to by the Assembly in Manila in 1986 was "to work towards the development of a model code of values which reflect women's quest for equality and justice" as a prerequisite to the development of a Uniform Civil Code. Towards this end, the steering committee decided to organize a regional conference that would bring together women in the Asia Pacific to draft a charter of values that would serve as guide for policies and laws affecting women. The conference aimed to set standards that would harmonize, if not unify, policies and laws for women in the Asia Pacific region. The conference also served as an opportunity for APWLD members to personally meet and strengthen the network solidarity.

Forty-two women from thirteen countries participated in the Code of Values Conference in Kuala Lumpur in November 1988. The conference proceeded smoothly in a highly participatory fashion. Participants contributed ideas and served as documenters and facilitators. A Charter of Values was drafted and action strategies for the consideration, recognition and adoption of the Charter were proposed by the participants. In spite of the diversity of culture, religion, and political systems, deliberations among the conferees revealed at least four bases of unity:

I attended the consultations and the South Asia legal literacy workshop in 1989, although my presence through OEF became less frequent. OEF and I continued to maintain a supportive relationship with APWLD. Some of the founders of APWLD would eventually be invited to be on the board of Women, Law and Development International, the organization that emerged from the OEF/WLD program and would continue to be an international WLD link with APWLD. In the meantime, my attention turned to Africa and Latin America in their bid to establish their own regional organizations.

The Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development was off to a strong, independent, dynamic start.

The steering committee offered the position of regional coordinator to one of its own members, Emelina Quintillan from the Philippines. She accepted the position and relocated to Kuala Lumpur at the end of the year, 1987, one year after the founding conference in Tagaytay. The APWLD office, which they called the secretariat, opened in January, 1988 in the Asia Pacific Development Center building, two stories up from Noeleen Heyzer's office and the APDC Women's Programme. Shanthi Dairium, an activist with Women's Aid in Kuala Lumpur joined Emelina on staff as program associate. In my consultative role, I spent several weeks during 1988 in Kuala Lumpur assisting the fledging staff in their task of organization and program development.

During its first year the APWLD staff divided its work between institution-building activities and program implementation. Its list of priorities for 1988 included developing effective communication between staff and steering committee and fund-raising for the administrative expenses needed for its operation. Initially, the tasks of the secretariat centered on:

- Establishing the legal status of APWLD;

- Setting up the infrastructure (personnel, equipment, office administrative systems, etc;

- Establishing linkages with all members of the Forum;

- Cataloging available expertise (locally and abroad) and establishing linkages;

- Identifying other agencies regionally and internationally from whom information and materials can be obtained on regular basis;

- Drawing up of detailed work plans.

In addition to gathering information and data about country situations, pertinent to threats against women's rights, the APWLD collaborated with 25 other women's organizations filing a suit with the Supreme Court of India against 'Sati'. In another gesture of solidarity, APWLD supported its Pakistani Steering Committee member, Asma Jahangir, who provided legal services in seeking the release of women, men, and children who were bonded brick kiln workers in Lahore, Pakistan. With a view to awareness raising and mobilization during its first year, APWLD drafted and disseminated a resolution calling on all women to be vigilant against retrogressive policies and enjoining parliamentarians to assume their duty of safeguarding the rights won by and for women. The resolution was disseminated widely and published in newspapers and newsletters across the region. Staff and steering committee members also provided technical assistance to local organizations in developing tools for policy analysis, setting up legal literacy programs, providing advice and referrals on matters related to women and development, law and development, and women and law, and facilitating the exchange of materials and inter-organizational meetings among the members.

One of the objectives agreed to by the Assembly in Manila in 1986 was "to work towards the development of a model code of values which reflect women's quest for equality and justice" as a prerequisite to the development of a Uniform Civil Code. Towards this end, the steering committee decided to organize a regional conference that would bring together women in the Asia Pacific to draft a charter of values that would serve as guide for policies and laws affecting women. The conference aimed to set standards that would harmonize, if not unify, policies and laws for women in the Asia Pacific region. The conference also served as an opportunity for APWLD members to personally meet and strengthen the network solidarity.

Forty-two women from thirteen countries participated in the Code of Values Conference in Kuala Lumpur in November 1988. The conference proceeded smoothly in a highly participatory fashion. Participants contributed ideas and served as documenters and facilitators. A Charter of Values was drafted and action strategies for the consideration, recognition and adoption of the Charter were proposed by the participants. In spite of the diversity of culture, religion, and political systems, deliberations among the conferees revealed at least four bases of unity:

- Gender - particularly around the issues of male violence against women and issues around reproduction, motherhood and parenthood;

- Patriarchal relationships - particularly in the area of marriage, family, divorce, religion, and other social institutions;

- State - particularly pertaining to legal rights, property ownership, division and distinction between public and private spheres of life, and modalities of development;

- Mutual support in crisis situations - the recognition of the necessity of solidarity, mutual support and fairness.

I attended the consultations and the South Asia legal literacy workshop in 1989, although my presence through OEF became less frequent. OEF and I continued to maintain a supportive relationship with APWLD. Some of the founders of APWLD would eventually be invited to be on the board of Women, Law and Development International, the organization that emerged from the OEF/WLD program and would continue to be an international WLD link with APWLD. In the meantime, my attention turned to Africa and Latin America in their bid to establish their own regional organizations.

The Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development was off to a strong, independent, dynamic start.

Continue on to Latin America and CLADEM, the second of the networks to develop.