Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras

Different realities, different problems, different analyses, different approaches.

The Project

In 1979 the Overseas Education Fund of the League of Women Voters (OEF), based in Washington DC, initiated a program to address the legal needs of women in the Central American countries of Costa Rica, Nicaragua and Honduras during a time of considerable instability in the region. I was hired to coordinate this project

with partner organizations in the three countries, in particular, the Federation of Women’s Associations, (FAFH), in Honduras, the Association of Nicaraguan Women "Luisa Amanda Espinoza" (AMNLAE), in Nicaragua and ASODELFI and several other women’s organizations in Costa Rica that had enjoyed earlier association with OEF.

The original design of this endeavor envisioned legal aid offices established in each country to assist women who might have need of such services. Although the organizations were quite eager to launch such services, I suggested that they take the first few months to do a needs assessment to make sure that the services they planned to offer would be what was truly needed for their context.

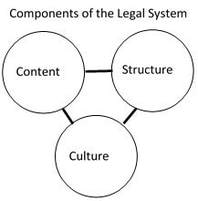

Through a series of workshops in each country, I introduced the groups to a simple, but powerful, framework elaborated by the legal scholar, Lawrence Freidman, that looked at the law as a “system,” composed of substantive, structural and cultural elements. Using this tool to assist them in their contextual analysis, the groups began to explore how each of those elements of the socio-legal system related to women in their counties. Additional interactive workshops with the organizations on effective programming supplemented the research they were conducting. It soon became clear that although Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica shared much in common, (similar legal systems, cultural attitudes, common areas of discrimination), the legal needs of women were unique to each country due to the unique socio-political situation of each.

In 1979 the Overseas Education Fund of the League of Women Voters (OEF), based in Washington DC, initiated a program to address the legal needs of women in the Central American countries of Costa Rica, Nicaragua and Honduras during a time of considerable instability in the region. I was hired to coordinate this project

with partner organizations in the three countries, in particular, the Federation of Women’s Associations, (FAFH), in Honduras, the Association of Nicaraguan Women "Luisa Amanda Espinoza" (AMNLAE), in Nicaragua and ASODELFI and several other women’s organizations in Costa Rica that had enjoyed earlier association with OEF.

The original design of this endeavor envisioned legal aid offices established in each country to assist women who might have need of such services. Although the organizations were quite eager to launch such services, I suggested that they take the first few months to do a needs assessment to make sure that the services they planned to offer would be what was truly needed for their context.

Through a series of workshops in each country, I introduced the groups to a simple, but powerful, framework elaborated by the legal scholar, Lawrence Freidman, that looked at the law as a “system,” composed of substantive, structural and cultural elements. Using this tool to assist them in their contextual analysis, the groups began to explore how each of those elements of the socio-legal system related to women in their counties. Additional interactive workshops with the organizations on effective programming supplemented the research they were conducting. It soon became clear that although Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica shared much in common, (similar legal systems, cultural attitudes, common areas of discrimination), the legal needs of women were unique to each country due to the unique socio-political situation of each.

Honduras was under a military regime at that time, but about to transition to civilian government. The Honduran Legal Services (LS) team immediately targeted the severe deficiencies in Honduran family law and its overt discrimination against women. They determined that law reform—changing the content of the law—should be the focus of work for Honduras, not merely giving assistance to women within the current legal framework. With that in mind, Honduran team set out to draft and lobby for a new family code that would ensure women's equality within the legal system. The FAFH had a firm basis for this task, as some members had already identified areas of needed change, even before the LS project began. Doña Alba Alonzo de Quezada and Dr. Norma Marina Garcia spearheaded this effort with the support of women throughout the country. They were also assisted by the political opening that the transition to civilian rule provided. Many of the women had experience as either student or political activists, which meant that they had links to various political parties where they hoped to press their case. The Honduran strategy, thus, focused on drafting the language of the new legal code, organizing to gain popular support for their proposed legislation and lobbying the political parties to support their proposal.

Nicaragua was also in transition. The same year the project began, the Sandinista insurrection had succeeded in ousting the Somoza Dictatorship after 43 years in power. The country was in turmoil with struggles at many levels about how to shape the new government. AMNLAE, the national women's organization, had been part of the Sandinista resistance, so it was in a good position to begin to address the legal needs of women within the new context. There were, however, growing-pains within the organization, as few of them had actually focused on women in the struggle to overcome the atrocities of the dictatorship. Strong civil society organizations were almost non-existent during the Somoza era, so the AMNLAE leadership had very little experience managing a democratic, participatory organization. They were more familiar with authoritarian structures where decisions are made at the top.

Fortunately, AMNLAE's mentor and designated strategist for the LS project was Milú Vargas, who was also Legal Counsel for the Consejo de Estado, the legislative body of the newly formed government. Milú recognized that the AMNLAE team working on the project faced a daunting challenge. There had been no reform of the family code in Nicaragua since early in the 20th century. Like Honduras, women were highly disadvantaged in the legal sphere and, similarly, it made little sense in Nicaragua to provide legal aid to women based in such a discriminatory legal framework. Moreover, women in Nicaragua had little experience in the political aspect of law reform. It is one thing to draft a beneficial law, another to get it passed in the legislature and properly implemented within the judiciary and administrative agencies of the state. The entrenched “machismo” of the culture was another important factor to consider when constructing a strategy to change the law.

Under Milú's guidance the AMNLAE team decided that it would be best to begin with a single aspect of the family code, rather than tackling it in its entirety, and to begin with what was of concern to women themselves. After conducting a survey of women across the country, they discovered, surprisingly, that the adoptions law was of most concern to grassroots women due to the vast number of orphans left by the 1972 earthquake that devastated much of capital city of Managua and by the war against Somoza. These children were being cared for by relatives or others, but had very ambiguous legal status and few defined rights and entitlements.

Even though this law wouldn’t impact the status of women substantively, the AMNLAE team decided to start there. They knew the experience of coming up with needed changes, gaining public support for the changes and finally pressing their proposed law through the Council of State would provide a firm foundation for future changes to the family code. It was also a less threatening topic to the men who made up most of the membership of the legislative body. Following a successful change in the adoption law, they moved onto “patria potestad,” child custody. Here, women were clearly disadvantaged, as fathers retained total authority over the welfare of children in the family.

Costa Rica was the one stable liberal democratic society of the three. The organizations that formed part of the project came from a conventional strain of women’s organizations, most on the traditional, conservative side with regard to women and feminist views. They, like most Costa Ricans, prided themselves on their enlightened legislation and functioning democratic institutions. They felt that there was no need to reform laws and challenge the way they were applied; rather, the need for Costa Rican women was for legal assistance to make sure they received the benefit of their progressive laws. Their strategy was to open a legal aid office and to carry out an awareness raising program to educate women about their law.

Regional Dialog

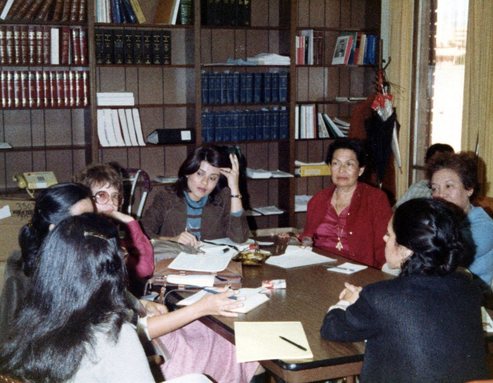

Central American Legal Services was a regional program involving three countries, not just three separate, unrelated projects. Holding inter-country meetings held every six months and rotating country venues with the five key personnel from each country project became a way to enhance its regional character and promote exposure to new ideas. The purpose of these encounters was the interchange of ideas, analyses, experiences, materials, etc. Productive exchange was not a simple task because of the ideological, cultural, analytical and experiential differences among them. Initially, there was considerable reticence among the participants from the different countries to open to the others, most feeling that their analysis of the issues and best approaches were superior to those of the rest. Of course, not everyone from each country thought alike, but in general that was the feeling.

The challenge for me, as facilitator, was one of devising a process so that each team could freely present its preferred theoretical or strategic framework and then sincerely listen to the others who might have a very different viewpoint. Some had a very clear feminist perspective, others had a desire to help women, but hadn't thought the problem through to any depth and the use of such terms as the "subordination of women" were somewhat alien to them. Regional workshops with expanded participation supplemented the twice-yearly meetings in order to introduce innovative ideas and different ways of looking at things. After a while personal relationships formed and a common framework and language began to be shared among them.

Building Analytical Skills

As the participants listened to one another they began to realize that whether they lived under a military, revolutionary or liberal government or whether their focus was on law reform or provision of legal aid, one thing they all had in common was that women did not know the rights they had, or even think of themselves as the subject of rights, even if the rights were clearly spelled out in law. Moreover, they recognized that successful law reform required an educated public ready to endorse change and a constituency of women aware of their status and willing to press their case. The importance of legal literacy and awareness raising began to take hold. And as they explored further, they realized that educating the police and judges was necessary too, if advantageous laws were to be properly enforced to women’s benefit.

Nicaragua was also in transition. The same year the project began, the Sandinista insurrection had succeeded in ousting the Somoza Dictatorship after 43 years in power. The country was in turmoil with struggles at many levels about how to shape the new government. AMNLAE, the national women's organization, had been part of the Sandinista resistance, so it was in a good position to begin to address the legal needs of women within the new context. There were, however, growing-pains within the organization, as few of them had actually focused on women in the struggle to overcome the atrocities of the dictatorship. Strong civil society organizations were almost non-existent during the Somoza era, so the AMNLAE leadership had very little experience managing a democratic, participatory organization. They were more familiar with authoritarian structures where decisions are made at the top.

Fortunately, AMNLAE's mentor and designated strategist for the LS project was Milú Vargas, who was also Legal Counsel for the Consejo de Estado, the legislative body of the newly formed government. Milú recognized that the AMNLAE team working on the project faced a daunting challenge. There had been no reform of the family code in Nicaragua since early in the 20th century. Like Honduras, women were highly disadvantaged in the legal sphere and, similarly, it made little sense in Nicaragua to provide legal aid to women based in such a discriminatory legal framework. Moreover, women in Nicaragua had little experience in the political aspect of law reform. It is one thing to draft a beneficial law, another to get it passed in the legislature and properly implemented within the judiciary and administrative agencies of the state. The entrenched “machismo” of the culture was another important factor to consider when constructing a strategy to change the law.

Under Milú's guidance the AMNLAE team decided that it would be best to begin with a single aspect of the family code, rather than tackling it in its entirety, and to begin with what was of concern to women themselves. After conducting a survey of women across the country, they discovered, surprisingly, that the adoptions law was of most concern to grassroots women due to the vast number of orphans left by the 1972 earthquake that devastated much of capital city of Managua and by the war against Somoza. These children were being cared for by relatives or others, but had very ambiguous legal status and few defined rights and entitlements.

Even though this law wouldn’t impact the status of women substantively, the AMNLAE team decided to start there. They knew the experience of coming up with needed changes, gaining public support for the changes and finally pressing their proposed law through the Council of State would provide a firm foundation for future changes to the family code. It was also a less threatening topic to the men who made up most of the membership of the legislative body. Following a successful change in the adoption law, they moved onto “patria potestad,” child custody. Here, women were clearly disadvantaged, as fathers retained total authority over the welfare of children in the family.

Costa Rica was the one stable liberal democratic society of the three. The organizations that formed part of the project came from a conventional strain of women’s organizations, most on the traditional, conservative side with regard to women and feminist views. They, like most Costa Ricans, prided themselves on their enlightened legislation and functioning democratic institutions. They felt that there was no need to reform laws and challenge the way they were applied; rather, the need for Costa Rican women was for legal assistance to make sure they received the benefit of their progressive laws. Their strategy was to open a legal aid office and to carry out an awareness raising program to educate women about their law.

Regional Dialog

Central American Legal Services was a regional program involving three countries, not just three separate, unrelated projects. Holding inter-country meetings held every six months and rotating country venues with the five key personnel from each country project became a way to enhance its regional character and promote exposure to new ideas. The purpose of these encounters was the interchange of ideas, analyses, experiences, materials, etc. Productive exchange was not a simple task because of the ideological, cultural, analytical and experiential differences among them. Initially, there was considerable reticence among the participants from the different countries to open to the others, most feeling that their analysis of the issues and best approaches were superior to those of the rest. Of course, not everyone from each country thought alike, but in general that was the feeling.

The challenge for me, as facilitator, was one of devising a process so that each team could freely present its preferred theoretical or strategic framework and then sincerely listen to the others who might have a very different viewpoint. Some had a very clear feminist perspective, others had a desire to help women, but hadn't thought the problem through to any depth and the use of such terms as the "subordination of women" were somewhat alien to them. Regional workshops with expanded participation supplemented the twice-yearly meetings in order to introduce innovative ideas and different ways of looking at things. After a while personal relationships formed and a common framework and language began to be shared among them.

Building Analytical Skills

As the participants listened to one another they began to realize that whether they lived under a military, revolutionary or liberal government or whether their focus was on law reform or provision of legal aid, one thing they all had in common was that women did not know the rights they had, or even think of themselves as the subject of rights, even if the rights were clearly spelled out in law. Moreover, they recognized that successful law reform required an educated public ready to endorse change and a constituency of women aware of their status and willing to press their case. The importance of legal literacy and awareness raising began to take hold. And as they explored further, they realized that educating the police and judges was necessary too, if advantageous laws were to be properly enforced to women’s benefit.