Human Rights Advanced Leadership Training

Central and Eastern Europe and the Newly Independent States

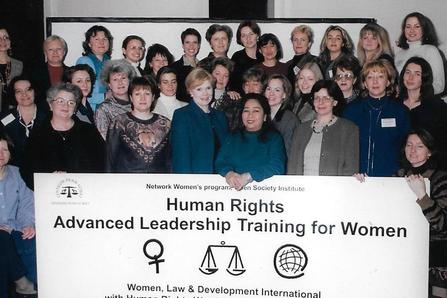

WLDI launched the Advanced Human Rights Leadership Training program for women in Central and Eastern Europe and the Confederation of Independent States in 1998 with the support of the Soros Foundation (Open Society Institute). Its Network Women's Program was the vehicle for collaboration and financial support for program.

Anastasia Posadskaya, head of the newly formed program, recognized that in the period following the fall of the Soviet Union, the situation of women in post-socialist countries was characterized by a deterioration of status and violation of rights, including “a predominance of poor and unemployed women, increased violence against women, heightened sexism in the mass media and culture, discrimination against women in the realms of economics and education, as well as more than 20 military conflicts in the region, which took a horrifying, gender-specific toll on women.” *

She also recognized how the concerns of these women were left out of the deliberations at the Women’s Conference in Beijing and its premier document, the Beijing Platform for Action. From my own experience, it was clear that the women of the region had not been part of the preparatory process for the 1995 UN Women's Conference. I had given a presentation in early 1995 to leaders of the women's movement in Russia explaining what the UN Women's Conference and the NGO Forum were all about. These leaders were amazed to learn this, as they had no idea about the workings of the UN or how NGO's could make their concerns known. As Posadskaya noted "the new NGO's did not have the training they needed to translate their experience into the language of the international document."* By the time of the Conference in Beijing a group of women from Bulgaria, Russia, Poland and Ukraine had drafted a "Statement from a Non-Region," highlighting their situation of invisibility, lack of resources and disempowerment.

The 1997 publication of the human rights manual, Women’s Human Rights Step by Step reinforced OSI’s belief in the probability of women’s empowerment through access to international instruments and mechanisms. This opened up the possibility of collaboration between WLDI and OSI on an unprecedented capacity building effort among the new women’s movements in the post-socialist counties. After a complicated process of engaging the newly forming Open Society foundations across the region in understanding the content and process of the WLDI training, WLDI was given the go ahead and financial support to implement the program.

We added two staff members to work on this project. Emelina Quintillan came on as coordinator and Russian-speaking Galina Venetictova as project assistant. Trainers for the project included Nancy Flowers, Molly Reilly, Reagan Ralph, Joe Eldridge, Martina Vandenberg, Emelina and me.

The project began with the selection of 4 to 6 participants from 22 countries for a total of 120 participants. The countries included were:

Anastasia Posadskaya, head of the newly formed program, recognized that in the period following the fall of the Soviet Union, the situation of women in post-socialist countries was characterized by a deterioration of status and violation of rights, including “a predominance of poor and unemployed women, increased violence against women, heightened sexism in the mass media and culture, discrimination against women in the realms of economics and education, as well as more than 20 military conflicts in the region, which took a horrifying, gender-specific toll on women.” *

She also recognized how the concerns of these women were left out of the deliberations at the Women’s Conference in Beijing and its premier document, the Beijing Platform for Action. From my own experience, it was clear that the women of the region had not been part of the preparatory process for the 1995 UN Women's Conference. I had given a presentation in early 1995 to leaders of the women's movement in Russia explaining what the UN Women's Conference and the NGO Forum were all about. These leaders were amazed to learn this, as they had no idea about the workings of the UN or how NGO's could make their concerns known. As Posadskaya noted "the new NGO's did not have the training they needed to translate their experience into the language of the international document."* By the time of the Conference in Beijing a group of women from Bulgaria, Russia, Poland and Ukraine had drafted a "Statement from a Non-Region," highlighting their situation of invisibility, lack of resources and disempowerment.

The 1997 publication of the human rights manual, Women’s Human Rights Step by Step reinforced OSI’s belief in the probability of women’s empowerment through access to international instruments and mechanisms. This opened up the possibility of collaboration between WLDI and OSI on an unprecedented capacity building effort among the new women’s movements in the post-socialist counties. After a complicated process of engaging the newly forming Open Society foundations across the region in understanding the content and process of the WLDI training, WLDI was given the go ahead and financial support to implement the program.

We added two staff members to work on this project. Emelina Quintillan came on as coordinator and Russian-speaking Galina Venetictova as project assistant. Trainers for the project included Nancy Flowers, Molly Reilly, Reagan Ralph, Joe Eldridge, Martina Vandenberg, Emelina and me.

The project began with the selection of 4 to 6 participants from 22 countries for a total of 120 participants. The countries included were:

|

Albania

Armenia Azerbaijan Belarus Bosnia-Herzegovina Bulgaria Croatia, |

Czech Republic

Georgia Kazakhstan Kyrgyzstan Lithuania Macedonia Mongolia Poland |

Russia

Tajikistan Turkmenistan Ukraine Uzbekistan Yugoslavia Roma Community in Romania. |

The Process

Participants were divided into four groups by country, each of which participated in three one-week training workshops over a period of two years, for a total of 12 week-long training sessions. Several of the sessions took place at the Central European University in Budapest, Hungary, but others were held in Poland, Russia, Bulgaria, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Mongolia. In keeping with program goals and methodology explained on the previous page, the sessions covered core human rights and advocacy content with attention to the particular needs of the region. In the six months between sessions, participants applied the learning by refining and carrying out an actual strategy related to the issue they had identified during the first week.

Language was one of the challenges we faced in the program. The trainers were English speakers and so the participants had to be fairly fluent in English. but some struggled a bit. Because most participants spoke Russian, those who were not fully comfortable in English were assisted by the bilingual English Russian participants. The facilitators, most of whom had experience training groups in international settings, made it a priority to use non-idiomatic English as much as possible. Small group work sessions, composed of country teams, was carried out in their own languages. Following the program, the Step by Step manual was translated into most of the local languages of the region with the support of the Open Society Foundations.

Components of the Project

Training Sessions

Cycle one training concentrated on

Implementation of strategies by participants during the interim between sessions.

Technical assistance to the advocacy teams was ongoing through electronic mail, telephone, and fax. In addition, nine countries received on-site technical assistance visits to:

Participants were divided into four groups by country, each of which participated in three one-week training workshops over a period of two years, for a total of 12 week-long training sessions. Several of the sessions took place at the Central European University in Budapest, Hungary, but others were held in Poland, Russia, Bulgaria, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Mongolia. In keeping with program goals and methodology explained on the previous page, the sessions covered core human rights and advocacy content with attention to the particular needs of the region. In the six months between sessions, participants applied the learning by refining and carrying out an actual strategy related to the issue they had identified during the first week.

Language was one of the challenges we faced in the program. The trainers were English speakers and so the participants had to be fairly fluent in English. but some struggled a bit. Because most participants spoke Russian, those who were not fully comfortable in English were assisted by the bilingual English Russian participants. The facilitators, most of whom had experience training groups in international settings, made it a priority to use non-idiomatic English as much as possible. Small group work sessions, composed of country teams, was carried out in their own languages. Following the program, the Step by Step manual was translated into most of the local languages of the region with the support of the Open Society Foundations.

Components of the Project

Training Sessions

Cycle one training concentrated on

- The human rights system, instruments and mechanisms

- Strategies and the legal system,

- Human rights advocacy

- Developing a strategy

- The workshop in Kazakhstan explored trafficking, political rights, rights education and women's access to economic resources and social benefits.

- The workshop in Mongolia examined issues of labor rights and the effects of globalization on women.

- The workshop in Belarus focused on violence against women.

Implementation of strategies by participants during the interim between sessions.

Technical assistance to the advocacy teams was ongoing through electronic mail, telephone, and fax. In addition, nine countries received on-site technical assistance visits to:

- follow-up and assess the advocacy strategies designed by the participants during the workshops;

- help the participants refine their action plan for fund-raising and for effectiveness; and

- identify the obstacles and potential for making progress in the national contexts of the participants.

Documentation and Publication of the Strategies

Each of the teams was required to write a case study of their strategy by describing and analyzing their advocacy experience. The purpose of this exercise was to encourage organizers of the strategy to reflect, analyze and learn from the experience and, thus, consolidate the learning from the course.

"Becoming and Advocate Step by Step"

The publication of the case studies was the final component of the project. In September 2002, WLDI published the book, Becoming an Advocate Step by Step that contained twelve of the case studies prepared by the participants.

The process of writing the case studies and publishing them was regarded as essential to the entire training exercise. Not only did the writing contribute to solidifying the learning from the program, but it had the potential of making a contribution beyond the program. Documentation of advocacy experiences about women's rights was virtually non-existent in the CEE/CIS region. This absence served to guarantee the continuing invisibility of women's efforts across the region to use the human rights system creatively to uphold women's rights. Lack of documentation also created a practical problem for trainers who were forced to rely on advocacy case histories from other parts of the world that may have been less than fully relevant.

Thus, the exercise of analyzing their experiences in the program allowed participants to contribute to

Each of the teams was required to write a case study of their strategy by describing and analyzing their advocacy experience. The purpose of this exercise was to encourage organizers of the strategy to reflect, analyze and learn from the experience and, thus, consolidate the learning from the course.

"Becoming and Advocate Step by Step"

The publication of the case studies was the final component of the project. In September 2002, WLDI published the book, Becoming an Advocate Step by Step that contained twelve of the case studies prepared by the participants.

The process of writing the case studies and publishing them was regarded as essential to the entire training exercise. Not only did the writing contribute to solidifying the learning from the program, but it had the potential of making a contribution beyond the program. Documentation of advocacy experiences about women's rights was virtually non-existent in the CEE/CIS region. This absence served to guarantee the continuing invisibility of women's efforts across the region to use the human rights system creatively to uphold women's rights. Lack of documentation also created a practical problem for trainers who were forced to rely on advocacy case histories from other parts of the world that may have been less than fully relevant.

Thus, the exercise of analyzing their experiences in the program allowed participants to contribute to

- increasing understandings about designing, carrying out and analyzing a strategy among other advocates working on similar issues,

- developing comparative reviews of different experiences to draw out specific themes, challenges, opportunities and recommendations, and

- making visible the learning that emerged from the collective process of carrying out and evaluating the impact of women's human rights advocacy strategies in order to guide the work and thinking not only of activists, but scholars, donors and policy-makers.

In March 2000, WLDI convened a three-day analytical meeting in Moscow with the key drafter of each of the case studies selected for publication to conduct a final analysis and refinement of the case studies and to draw out regional themes from the participants' advocacy experience. The book was published by September, 2000, in time for the Beijing Plus Five meeting in New York. During that meeting, WLDI convened two panels of case study writers to share their results.