Advanced Human Rights Advocacy Training for Women

Antecedents

The WLDI Human Rights Advocacy Training program grew out of our commitment to serve the needs of the international network of women's rights advocates and our realization that we were all limited in our understanding of human rights concepts and human rights advocacy. Educational resources for those wishing to promote and defend women’s rights were particularly sparse. Few of us knew how to access the human rights system, how to influence it or how to use human rights concepts and instruments to influence the policies and practices of our national governments. As the organizers of the “comfort women” strategy in Korea and the Philippines tell their story, for example, they did not know exactly what do to or where to go to get satisfaction. The roadmap they left was the result of reflective action and an enormous willingness to learn.

The challenge to early women’s human rights advocates lay in learning to use international instruments and mechanisms to foster change and hold national and local authorities accountable for violations of women’s rights. Meeting this challenge demanded focus on concrete, practical strategies and approaches for translating the lofty language of international human rights commitments into tangible improvements in women’s lives. In a dynamic context of learning stimulated by necessity, women forged ahead and achieved impressive gains in recognition of women’s human rights at the international level. Analyzing the process of doing so opened up some important insights about human rights and how to use the system effectively at the international level.

What we learned is that progress occurred— on violence against women, for example— because women vigorously engaged the system by requiring it to respond to women’s reality, experiences and needs. Engaging the system meant getting its attention, obliging it to listen, requiring it to act on its own principles and insisting on a response. Over a period of fifteen years, the emerging women’s rights movement persevered in reinterpreting human rights traditionally thought not to apply to women (interpreting the right to bodily integrity, for example, to include protection from domestic violence.) In doing so, the movement has expanded to some degree the sphere of state responsibility and recently increased the power of international mechanisms to monitor government actions and omissions related to women’s human rights. Participation in the system and the worldwide mobilization under the motto of claiming “women’s rights as human rights” had a fundamental and transformative effect on the human rights agenda by pushing boundaries and altering ever so slightly the frontiers of the debate.

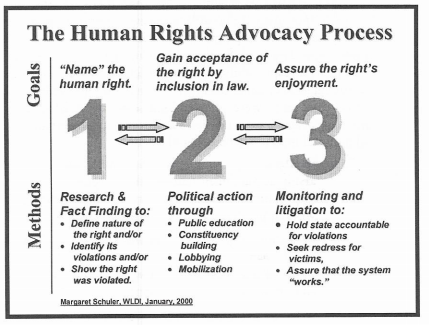

In studying this experience we discovered that the dynamics of pushing the boundaries require intervention in several ways and at several points in the achievement of three critical targets: expanding the definition of human rights, expanding the scope of state responsibility and expanding the effectiveness of the human rights system to enforce women’s rights.* We learned that these successes were achieved because women’s rights advocates took decisive action in various ways at both international and national levels. We recognized that:

The WLDI Human Rights Advocacy Training program grew out of our commitment to serve the needs of the international network of women's rights advocates and our realization that we were all limited in our understanding of human rights concepts and human rights advocacy. Educational resources for those wishing to promote and defend women’s rights were particularly sparse. Few of us knew how to access the human rights system, how to influence it or how to use human rights concepts and instruments to influence the policies and practices of our national governments. As the organizers of the “comfort women” strategy in Korea and the Philippines tell their story, for example, they did not know exactly what do to or where to go to get satisfaction. The roadmap they left was the result of reflective action and an enormous willingness to learn.

The challenge to early women’s human rights advocates lay in learning to use international instruments and mechanisms to foster change and hold national and local authorities accountable for violations of women’s rights. Meeting this challenge demanded focus on concrete, practical strategies and approaches for translating the lofty language of international human rights commitments into tangible improvements in women’s lives. In a dynamic context of learning stimulated by necessity, women forged ahead and achieved impressive gains in recognition of women’s human rights at the international level. Analyzing the process of doing so opened up some important insights about human rights and how to use the system effectively at the international level.

What we learned is that progress occurred— on violence against women, for example— because women vigorously engaged the system by requiring it to respond to women’s reality, experiences and needs. Engaging the system meant getting its attention, obliging it to listen, requiring it to act on its own principles and insisting on a response. Over a period of fifteen years, the emerging women’s rights movement persevered in reinterpreting human rights traditionally thought not to apply to women (interpreting the right to bodily integrity, for example, to include protection from domestic violence.) In doing so, the movement has expanded to some degree the sphere of state responsibility and recently increased the power of international mechanisms to monitor government actions and omissions related to women’s human rights. Participation in the system and the worldwide mobilization under the motto of claiming “women’s rights as human rights” had a fundamental and transformative effect on the human rights agenda by pushing boundaries and altering ever so slightly the frontiers of the debate.

In studying this experience we discovered that the dynamics of pushing the boundaries require intervention in several ways and at several points in the achievement of three critical targets: expanding the definition of human rights, expanding the scope of state responsibility and expanding the effectiveness of the human rights system to enforce women’s rights.* We learned that these successes were achieved because women’s rights advocates took decisive action in various ways at both international and national levels. We recognized that:

- the definition of human rights expanded as women’s scholarship and activism achieved the acceptance of a reinterpretation of human rights to address the rights of women previously excluded from the definition;

- the sphere of government responsibility for the defense of women’s human rights expanded as women articulated states’ obligations to respect women’s human rights and engaged the state to comply; and finally

- the ability and willingness of the human rights system to enforce women’s human rights also expanded as women engaged the human rights system and required it to take measures to stop, remedy, or otherwise solve problems of violations of women’s human rights.

In 1997, WLDI in collaboration with Human Rights Watch Women's Rights Project published the manual Women's Human Rights Step by Step. This manual provides a simple and practical explanation of the concepts and content of human rights law and its application to women. Using Step by Step as a framework, WLDI launched a program to help women leaders around the world deepen their understanding of gender, rights and advocacy.

This initiative got underway in the region of Central and Eastern Europe and Newly Independent States in 1998 involving more than 120 women activists from twenty-two countries. The program began in Central and East Africa in March 1999, in Indonesia in 2001 and in Nigeria in 2003.

Goals and Objectives

The overall goal of Human Rights Advocacy Training program was to strengthen the skills and capacities of front line advocacy groups to design, carry out and analyze the impact of women's human rights advocacy strategies with the aim of developing institutional advocates for women’s rights within national, regional and international fora. In addition, the program sought to develop their skills as trainers and educators, guiding and orienting other activists and constituents toward effective women’s rights advocacy.

The specific objectives of the project:

This initiative got underway in the region of Central and Eastern Europe and Newly Independent States in 1998 involving more than 120 women activists from twenty-two countries. The program began in Central and East Africa in March 1999, in Indonesia in 2001 and in Nigeria in 2003.

Goals and Objectives

The overall goal of Human Rights Advocacy Training program was to strengthen the skills and capacities of front line advocacy groups to design, carry out and analyze the impact of women's human rights advocacy strategies with the aim of developing institutional advocates for women’s rights within national, regional and international fora. In addition, the program sought to develop their skills as trainers and educators, guiding and orienting other activists and constituents toward effective women’s rights advocacy.

The specific objectives of the project:

- To develop a corps of women’s human rights advocates with solid skills and capacities in training, planning, coordination and analysis;

- To build the capacity of civil society—and women’s organizations in particular—to use the human rights framework as a tool to advocate for greater responsiveness to women’s needs and concerns;

- To impact the laws, policies and practices of national and local government authorities to bring them into line with human rights norms; and

- To strengthen the human rights system by promoting greater government transparency and accountability to women’s demands and concerns

Content

The challenge to any new human rights advocate consists of learning to use international instruments and mechanisms to foster change and hold national and local authorities accountable for violations of women’s rights. In developing our program we attempted to systematize our learnings and develop a body of knowledge gleaned from the practice of those who had already broken ground in this field. As facilitators of the process we were challenged to identify the central and most indispensable concepts an advocate would need to:

Learning human rights advocacy requires a focused effort to sort out the multitude of facts and information available, identify relationships among them and select those most relevant. In our training program we emphasized advocacy-grounded human rights content with special attention to deepening the conceptual understanding of the participants about:

The challenge to any new human rights advocate consists of learning to use international instruments and mechanisms to foster change and hold national and local authorities accountable for violations of women’s rights. In developing our program we attempted to systematize our learnings and develop a body of knowledge gleaned from the practice of those who had already broken ground in this field. As facilitators of the process we were challenged to identify the central and most indispensable concepts an advocate would need to:

- identify a human rights issue,

- propose a policy solution using the human rights framework (instruments and mechanisms),

- design a strategy capable of achieving the proposed solution, and

- apply the skills needed to implement the strategy.

Learning human rights advocacy requires a focused effort to sort out the multitude of facts and information available, identify relationships among them and select those most relevant. In our training program we emphasized advocacy-grounded human rights content with special attention to deepening the conceptual understanding of the participants about:

- the main concepts of human rights law;

- the structure and process of the human rights system;

- human rights advocacy skills and concepts;

- practical steps needed to plan, carry out and evaluate an advocacy strategy focused on a women's human rights issue.

In this context, we gave particular importance to defining of key concepts. For example: What is a “right”? What is a “human right”? What is a “woman’s human right”? What does it mean to work in the “human rights framework”? At the beginning of our training, most participants were hard pressed to sort out the differences. “Advocacy,” another critical concept, is often incorrectly understood as “lobbying.” Unless advocates have these distinctions firmly fixed, their choice of issues, their goals and their strategies can all suffer. Indefensible arguments and misplaced energies can be the result.

We also placed emphasis on the dynamics of human rights development in a contemporary context. The critique of human rights as a project of the Enlightenment, and therefore irrelevant to non-Western societies, is bolstered by a view that overvalues the roots of modern human rights in remote European philosophical traditions. By analyzing contemporary examples of how “new” rights have been named and clarified and how governments have been held to account for their actions, key concepts of human rights can be made functional to the advocate in a way a traditional approach could not.

There are two central ideas that if internalized inspire activists to identify themselves as— and to be— central to the human rights dynamic. First, is the idea that the expansion and refinement of human rights content (including both the nature of the right and what constitutes a violation) is an on-going process of consensus-building. Second, is the understanding that advocates can be (indeed have been) successful in achieving consensus on important issues. The processes of gaining recognition of violence against women as a human rights violation or rape in conflict situations as a crime against humanity are both dynamic examples of using contemporary experiences to clarify the role of the advocate in human rights and inspire their activism.

Finally, we emphasized the link between advocacy as a process and the dynamics of human rights. This implies understanding the local-global relationship, that is, the conditions under which advocacy can be defined as “human rights advocacy,” whether at the local or national level.

In sum, all of the program’s content was chosen to increase the capacity of advocates to understand:

We also placed emphasis on the dynamics of human rights development in a contemporary context. The critique of human rights as a project of the Enlightenment, and therefore irrelevant to non-Western societies, is bolstered by a view that overvalues the roots of modern human rights in remote European philosophical traditions. By analyzing contemporary examples of how “new” rights have been named and clarified and how governments have been held to account for their actions, key concepts of human rights can be made functional to the advocate in a way a traditional approach could not.

There are two central ideas that if internalized inspire activists to identify themselves as— and to be— central to the human rights dynamic. First, is the idea that the expansion and refinement of human rights content (including both the nature of the right and what constitutes a violation) is an on-going process of consensus-building. Second, is the understanding that advocates can be (indeed have been) successful in achieving consensus on important issues. The processes of gaining recognition of violence against women as a human rights violation or rape in conflict situations as a crime against humanity are both dynamic examples of using contemporary experiences to clarify the role of the advocate in human rights and inspire their activism.

Finally, we emphasized the link between advocacy as a process and the dynamics of human rights. This implies understanding the local-global relationship, that is, the conditions under which advocacy can be defined as “human rights advocacy,” whether at the local or national level.

In sum, all of the program’s content was chosen to increase the capacity of advocates to understand:

- issues to consider and decisions to make when crafting a women's human rights advocacy strategy;

- critical components of an advocacy strategy;

- gender and its relation to human rights advocacy;

- power and tools for analyzing power relationships affecting an advocacy strategy

- constituency building as a part of an advocacy strategy;

- the role of research in developing a strategy;

- creative ways to use human rights instruments and mechanisms as advocacy tools; and

- how to do rigorous fact-finding and documentation of violations as well as to monitor ongoing human rights performance.